Somewhere above 35,000 feet, I found myself in an unexpected debate with a partner at a major accounting firm. His firm, like many others, had embraced AI-powered tools to digitize receipts with just a camera scan.

I wondered how much time, energy and effort went into this process. Data has to be collected, cleaned, and structured. AI models must be trained, deployed, and continuously monitored for relevance. Now contrast that with parsing a well-structured receipt. Every invocation of an AI model requires appreciably more energy than parsing a structured response. Why do companies invest in high capex, energy-intensive AI workflows to solve a problem that could be eliminated at the source? How would AI ever compete with standardization?

It raised a question: Why don’t we just standardize receipts so we can skip the digital gymnastics altogether?

He chuckled. “We’re not in the business of pushing new standards.” That remark stuck with me. Why do we suffer inefficiency when the alternative is so seductively elegant?

The large variance in receipt formats persists because of inertia, misaligned incentives, and the natural complexity of large-scale systems. In theory, businesses should welcome streamlined formats that reduce costs and errors. In practice, switching to a new standard or creating a new standard is costly, and no single entity wants to bear that burden alone. Even when the benefits are obvious, standardization is hard to justify unless there’s a clear economic or strategic advantage.

Some standards, like the USB port or the metric system, unlock innovation by creating common ground. Others, like proprietary file formats or walled-off ecosystems, reinforce dominance by making alternatives costly. The question of standardization is about who gets to decide, what tradeoffs are baked in, and how much room remains for evolution.

Historically, standardization has played a crucial role in trade and the exchange of ideas. A shared language lowers barriers, improves coordination, and accelerates commerce. But standardization has always come with tradeoffs. Take the French suppression of Occitan: for centuries, Occitan thrived as a literary and cultural language across southern France. But as the French state centralized power, it imposed Parisian French as the national standard, systematically discouraging and even banning Occitan in schools. This made administration and governance more efficient, but it also erased a linguistic identity that had flourished for generations.

For generations, we solved coordination problems with standardization: roads, laws, languages, regulations, protocols. However, every standard is a blunt instrument, enforcing order at the expense of adaptability.

And that’s the Faustian bargain: standardization reduces chaos at the cost of flexibility. Between structure and fluidity, precision and accessibility, efficiency and resilience, every system we build is a compromise. Every law we write is a blunt instrument. Every standard is a balance between control and creativity. But what if instead of choosing between structure and flexibility, we could have both, without forcing artificial constraints?

Tradeoffs are not flaws of human systems; they are fundamental to how complex structures emerge. Cities, markets, ecosystems… none are truly centrally planned, yet they function through local interactions that self-organize into global patterns. When constraints are adaptive instead of rigid, systems become more resilient, more intelligent, more alive. The tragedy of standardization is that it replaces this organic intelligence with fixed rules. And typically, advances in technology have allowed us to make these constraints more adaptive.

Technology has consistently created slack to alleviate the effect of tradeoffs where competing priorities, technical limitations, and institutional inertia grind progress to a halt. Often, bottlenecks emerge not because solutions don’t exist, but because different stakeholders optimize for different things. Businesses want interoperability, but they also want proprietary advantages. Consumers want convenience, but they also (sometimes) want privacy. Every system is shaped not just by technical constraints, but by the tug-of-war between those who shape its incentives. Just as previous technological shifts redefined what was once considered an unavoidable compromise, AI will erode some of our most fundamental tradeoffs, replacing rigid binaries with adaptive, context-aware solutions.

Embeddings (a latent representation of the underlying information) and AI models offer a way out of these rigid choices. Instead of imposing a single standard, we can use AI to act as a real-time translation layer, allowing systems to remain diverse while still interoperating seamlessly. Large language models (LLMs) and AI embeddings can restructure and reformat information dynamically, adapting to the needs of each recipient. Businesses, institutions, and entire economies no longer have to choose between fragmentation and rigid standardization. AI is a lot more powerful today, but currently we use it to work around these rigid systems rather than rethinking them. Instead of asking AI to fix broken, fragmented workflows, why not use it to create more fluid, adaptive ones? The interesting question isn’t whether AI is a net positive. The interesting question is whether AI can loosen the grip of compromises we once saw as intrinsic to how the world works.

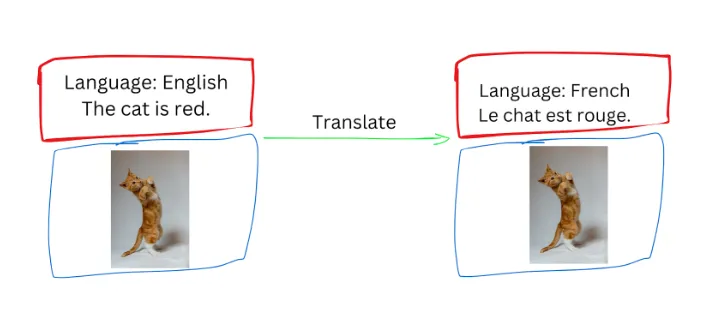

Take the standardization tradeoff between chaos and flexibility. Can we use AI as a translator to get the benefits of standardization while mitigating its risks? What if, instead of enforcing a single format, we allowed each system to speak its own language? Consider spoken language: we don’t force the world to speak a single tongue for efficiency’s sake. Instead, we translate.

The underlying ideas don’t change, only the way it’s described changes.

Consider how we consume information today. We all receive the same receipts, the same websites, the same ads - fixed formats designed for the majority. But if you and I consume information differently, why do we see the same websites? Some prefer reading, others listening, others skimming structured data or if you’re like me, you prefer allegorical folktales to explain how the world works. What if, instead of static formats, we received information that adapted to us?

More generally, can we decouple information from its presentation?

Imagine getting a receipt, but instead of a fixed PDF, you get this AI embedding that’s more flexible. If I prefer an audio version, the information is decoded into audio. If you need a table of raw data, the AI translator generates that from the embedding instead. The information is the same, but its presentation shifts to fit the user. This isn’t just a convenience upgrade - it’s a fundamental shift in how we interact with the digital world. And it isn’t just for consumers.

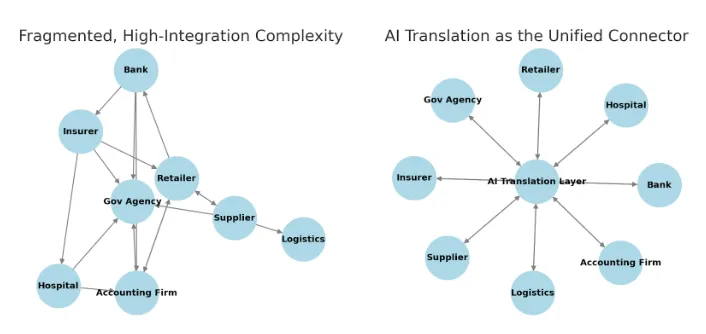

For businesses, this shift is equally powerful. Right now, companies spend vast amounts of time and money just making their systems talk to each other. Supply chain transactions, insurance claims, financial reports - every industry has its own formats, its own schemas, its own labyrinth of integrations. A retailer receives invoices in one format, but their accounting software expects another. A hospital shares medical data, but insurers demand it in a completely different structure. The result? A never-ending cycle of middleware, APIs, and translation layers, each solving a problem that shouldn’t exist in the first place.

Left: Fragmentation meant more middleware, more APIs, more headaches

Right: AI offers a different path: not another layer, but a bridge

This is where AI becomes more than just an automation tool. It’s connective tissue - quietly bridging fragmented systems without forcing a universal standard. It could make supply chains more resilient, financial regulations more adaptable, healthcare records more accessible, all by shifting the burden of translation from people to machines.

We don’t need more rigid standards. We need a way to make information fluid, adaptable, and deeply personal. AI translators offer that opportunity - not by imposing one way of doing things, but by allowing every system, every person, and every business to access information in the way that makes the most sense for them.

At its core, this isn’t just about making businesses more efficient, it’s about solving a broader coordination problem that affects entire economies. The U.S. economy, in particular, thrives on a juxtaposition: its relatively free market fuels competition and resilience, but also breeds inefficiency. This ethos is at the heart of the American economy: healthcare, finance, government, tech, insurance, education, and more, are all operating in fragmented silos. This free market ‘utopia’ is locally sub/optimal but holistically, it’s nonoptimal. Call them Canadian sensibilities but I was bewildered by American institutions and their success despite the chaos. But what seemed like pure dysfunction was actually just a byproduct of the free market. The same free market policies that make the American economy institutionally robust also make it inefficient.

Consider the healthcare industry. It’s famously fragmented, with private insurers, state-specific regulations, and myriad providers all doing things their own way. It’s incredibly frustrating for patients who have to navigate a maze of forms and coverage rules. But it’s also the same ecosystem where new surgical technologies, experimental treatments, and novel financing models can pop up rapidly (vs Canada). The messy, unregulated edges sometimes foster fresh ideas that might be stifled in a more centralized system.

So is there a way to retain the dynamism of the free market while not compromising efficiency? Some countries already actively structure their economies to minimize fragmentation through governance rather than technology. So what can we learn from them? How do countries that manage fragmentation perform? And is that something Americans et al. should aspire to?

If we look at smaller or highly centralized nations, e.g. Estonia or Singapore, efficiency is baked into their institutions. They have strong e-government infrastructures, streamlined public services, and top-down coordination that keeps fragmentation in check. These countries might not even feel the need for an AI “bridging function” quite as urgently, because they already minimize fragmentation through policy and planning. But in a place like the US, where the fragmentation is deeply embedded, an AI translator could turn that free-market-borne fragmentation into an advantage by allowing coherence without losing agility.

While AI can help fragmented economies like the U.S. regain coherence, developing nations face a different choice: they can avoid fragmentation internally by designing digital-first infrastructure from the start. For developing nations, the leapfrog potential is enormous. By adopting unified digital standards from the outset, they can leapfrog past the legacy infrastructure that burdens more developed countries.

Consider how Kenya’s M-Pesa revolutionized financial access - not by modernizing existing banks, but by skipping them entirely and moving straight to mobile payments. Or how some countries have built national digital ID systems that integrate seamlessly with government services, while antiquated bureaucracies like Germany’s still wrestle with snail mail, paper-based records and fragmented databases. Rather than retrofitting old systems, developing nations can design for interoperability from the start, avoiding the inefficiencies that wealthier countries now struggle to undo.

However, these countries still have to trade and interact with countries with varying levels of fragmentation, making the bridging function an inevitable necessity. And as AI’s capabilities in protein design, alternative energy, and other complex domains grow, everyone, from the smallest country to the largest, will eventually have to revisit how they invest in AI.

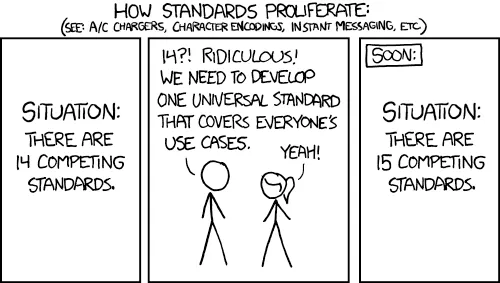

But fragmentation isn’t just a technological or economic challenge, it’s a fundamental reality of human systems, an inevitability of how we organize and interact with each other. Every attempt to unify, from trade agreements to digital protocols, comes with its own tensions. In fact, many of the most persistent forms of fragmentation - in tech, in policy, in culture - can be traced back to these fundamental tradeoffs, baked into the architecture of our institutions. The recursive irony is that explaining this compromise requires its own tradeoff. Even what you’re reading right now is a tradeoff between fidelity and accessibility! To make these ideas accessible, I’ve sacrificed nuance. For example, an OCR expert would remark on how VLM (vision-language models) struggle with reading receipts in ways that modern OCR would not. Or an economist like Ronald Coase might argue that AI would simply shift tradeoffs, not eliminate them. Or an AI researcher might similarly argue that if two systems interpret the same AI-generated representation slightly differently, do we simply shift the burden of misunderstanding rather than removing it? Or an engineer might ask if using AI as a translator just creates more standards and two parties, nevertheless, have to negotiate which AI model version to use? But that’s exactly the point: tradeoffs aren’t always a challenge to overcome, they’re sometimes an unavoidable reality of human decision-making.

(Courtesy of xkcd)

Human curiosity generates an insatiable demand for information - one that traditional knowledge systems struggle to meet efficiently. We ask questions faster than answers can be created. This mismatch between the demand for and supply of information creates fertile ground for misinformation to thrive, filling the gap with speculation or falsehoods. Tools like ChatGPT help bridge this gap, but they do so in ways that are institutionally different from traditional news services and legacy knowledge providers.

This particular tradeoff ripples outward, shaping how entire systems are built, how decisions are made, and how coordination breaks down at scale. Consider something as fundamental to our societies as our laws. Laws are constrained by the limits of human cognition. For example, if traffic laws are too intricate - i.e. high fidelity, we’d struggle to follow them but if they’re too simple, we risk inefficiencies, like when we stop at a red light at 3 a.m. with no cars in sight. We obey the red light even though there’s no societal cost to running the red light at 3 a.m. but there’s a personal cost to waiting. This contrived issue isn’t about overreach, it’s about how effectively we can dictate how we want our world to look.

If laws were written in a formal, provable language (instead of English), AI could dynamically interpret real-world scenarios (this is still an active area of research called scene understanding) and apply laws with machine-level precision. Self-driving cars, for example, wouldn’t just follow simplified human traffic laws, they could interpret a vast, highly detailed legal framework in real-time, optimizing for safety, efficiency, and energy use without requiring human judgment. Or imagine if AI-generated code could have compliance imbued in it. Or imagine an AI-driven corporate structuring tool that dynamically reconfigures a company’s legal and financial setup to optimize for newly announced incentives, subsidies, or tax breaks. This wouldn’t just change traffic, it would change how we govern everything. Instead of relying on rigid legal frameworks and human interpretation, we could express our collective vision in code - explicit, adaptable, and provable - and precisely write the world we want to create. AI wouldn’t just interpret laws, it would shape them in real time, aligning enforcement with intent, optimizing for safety, efficiency, and fairness in ways no static legal code ever could. While we have the right to a trial, the enormous backlog in the court systems effectively starves out anyone not rich enough to hold out for a trial.

Of course, this is not without risk, especially political risk. Who writes these machine-readable laws? Who decides what an algorithm considers fair? If AI personalizes the law itself by optimizing regulations in real time, does governance become hyper-responsive or hyper-political? If two people experience different tax policies, different contract terms, different enforcement based on AI-optimized outcomes, do we create a world of dynamic fairness or algorithmic feudalism? If AI personalizes economic rules, does that increase fairness or enable algorithmic favouritism? Is ambiguity unavoidable? AI’s ability to bridge fragmented systems is not just a technical feat but a harbinger of power redistribution: one that could entrench hierarchies as easily as it could dismantle them. In other words, will AI make institutions more responsive, or simply make inequality more efficient? Handled well, AI could do something we’ve never been able to: bend tradeoffs to our advantage instead of letting them dictate our choices. If American optimism can reckon with its original sin and still maintain its spirit of progress, then it must also aspire to be worthy of leading the world in a responsible and effective use of this technology.

Yet, for all its transformative potential, my humble opinion is that the broader AI discourse remains uninspired. Regulators fixate on containing big tech on one end while simultaneously trying to maintain an edge over geopolitical rivals, effectively stranding themselves on a tightrope. However, big tech, in many aspects, also lacks imagination as they treat AI as a mere productivity tool when it could be an architectural one, not just optimizing the world as it is, but reshaping the world as it could be.

Every generation has inherited their predecessors’ tradeoffs. AI won’t erase these tradeoffs, but it will let us navigate them in ways we’ve never been able to before. We stand at an inflection point. We are no longer bound by the tradeoffs of our predecessors. We have a tool to reshape them. If we let AI merely optimize old institutions, we will have built a machine to calcify the past. But if we use it to rethink our tradeoffs, to let emergence, not bureaucracy, shape the future, then for the first time, we won’t just inherit our world. We’ll be free to redesign it.

The real question isn’t just whether we can build a more fluid, emergent system. It’s whether we have the vision and will to do so.